Z5 — Time

Designing for both the predicted and unconsidered

Architecture is often perceived as a stable background that persists independently of time. It does, however, exist within rhythms of use, entropy, climate, and experience. We must design with these temporal phenomena.

‘We conceive of time as either flowing or as enduring.’ The notions of past, present, and future imply that time might ‘flow’, have a directional quality or be understood as a series of moments that are different but connected in some way. These properties, to which we might add change and flux, are the concerns of succession. Conversely we are aware that time has a certain ‘length’, whether this be an hour, day, or moment. Time, in this sense, ‘lasts’, endures, and has a persistence that could be described as duration.

Architecture might also be understood through this scaffold of succession and duration. Often viewed as having more in common with duration, than succession, architecture is frequently seen as a stable background in defiance of time, concerned with the maintenance of a single state and designed, in the words of Karsten Harries, as a ‘Deep defence against the terror of time.’ Inner spaces modulate the variable outside climate, the effects of which are countered through the use of hard-wearing, long- lasting materials. Often it tries ‘to stop time or at least give the illusion that time is suspended in stillness’. Such architecture is concerned with duration. In reality, a building will be subject to perpetual changes in its physical state, light, inhabitation, use, and interpretation. Architecture that seeks to engage with these properties and embraces their related rhythms is concerned with succession. The role of the architecture then becomes about working with the structures and rhythms of these phenomena.

The examples described below explore the way we have used time in a range of projects. It is not an exhaustive exploration of the possibilities of time in architecture but demonstrates a diversity of possible approaches possible to thinking with time in mind, to working with the predicted and unpredictable.

Event

Brickworks, a community centre we designed for Islington Council, is designed around a double height ‘inhabited lobby’ space which provides access to all parts of the building. From here visitors can access the surroundings facilities, including meeting rooms, a community hall, offices, community kitchen, and children’s playspace. As well as providing a way of navigating the building the lobby is designed to be able to host it’s own events, like the Chinese New Year celebrations seen here. It becomes more like a covered town square, an informal meeting point for the local population of the building, encouraging them to use it spontaneously. Compared to the programmed ‘timed’ spaces around its perimeter the lobby is a ‘prepared setting’ that prompts uses we could never predict.

Weathering

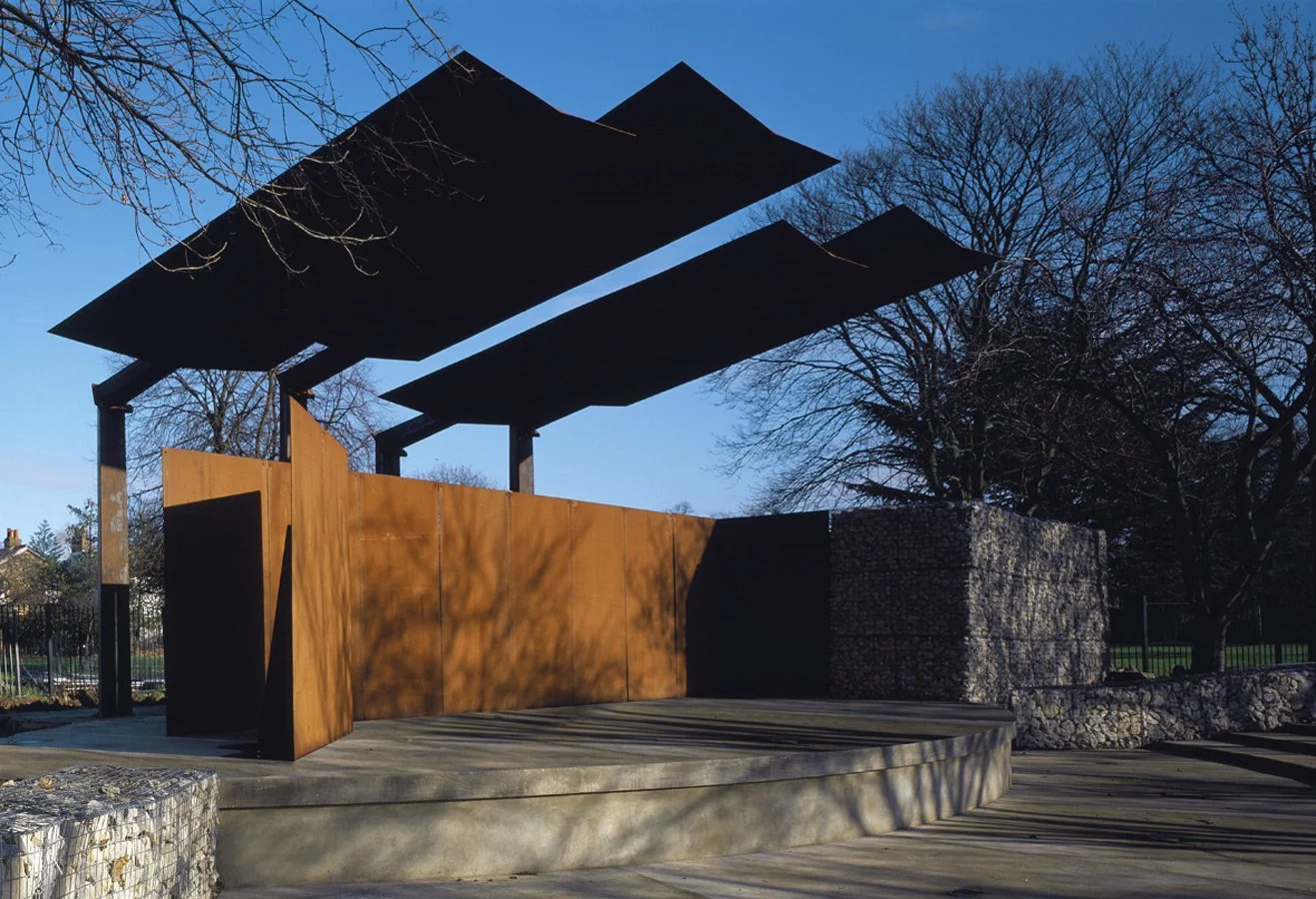

A new open air theatre structure we designed for the London Borough of Hillingdon replaces the original structure which was vandalised beyond repair. The new structure is made from cor-ten, weathering steel to absorb scratches and rough treatment. A tri-purpose store, changing room and back of house is formed from stone gabion baskets through which planting will intertwine. As the performance season is quite short the structure has an abstract, enigmatic quality when viewed across the park having sculptural and visual interest all year around.

Circadian rhythms

Our bodies internal biological clocks are re-set each day by the sun. These circadian rhythms are crucially important to help us regulate our activity and sleep-wake cycles. At Underwood Road, a housing project we designed for Peabody in Whitechapel all of the living spaces face due south, receiving sunlight throughout the day. Windows are designed to be full height and full width to maximise daylight within the space. However, the fenestration is combined with a carefully considered balcony which provides solar shading, to prevent overheating, and is formed from closely spaced vertical timber battens, some low to provide a view out and some full height to create some privacy. The thin timbers catch and sunlight and throw shadows across the balcony and interior. As the sun arcs across the sky the shadows wheel around the room giving a sense of the passing of time and an understanding of the time of day.

Moving parts

The simple insertion of a door into a wall creates the potential for numerous conditions. Alongside open and closed, it might be left ajar, creating a more nuanced relationship between one side and another. We enjoy exploiting the potential of moving parts in architecture, particularly where they can be controlled directly by the people who use them. In community centres we have included sliding screens in spaces, inhabited lobby spaces have been lined with doors and openings to give the choice of connection or withdrawal and double gates have been used similarly to modulate the relationship between a private yard and shared garden at Phoenix Heights.

A variation on the event space, combining both static and dynamic elements, is contained in a competition proposal we developed for a temporary ‘room’ on the rooftop of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, on the South Bank of the River Thames, London. The structure would exist for one year and be occupied by successive visitors for one day at a time. A reflective outer skin dematerialises the external form of the building, merging it with the changing weather and artificial light of the city at night. The room combines a fixed outer container, perforated with openings, with a moving inner platform, controlled by the occupant. As the platform rises its container frames and denies glimpses across the London skyline culminating in a panoramic roof terrace. Different heights give access to different facilities, light, views, and storage. The occupant chooses where within the container they want to rest. Perhaps they want some privacy, to be on show, to wake to the rising sun, to have some peace and stillness or to engage with city rhythms. The occupant decides, based on the choices offered by the room. Here dynamic elements, providing succession through changing spatial conditions and relationships with views, light, and facilities, are governed by a lived, spontaneous approach to time rather than an absolute temporal structure.

The text above draws on design-based research developed by Andrew Carr and published in a peer-reviewed paper in arq/Architectural Research Quarterly as The Quick and the Dead: Temporality, temporal structure and the architectural chronotope.