Z1 — The social life of space

In 2002, Robin Mallalieu and Angela Brady gave a lecture titled ‘The Social Life of Buildings’, relating how people use, occupy and experience buildings. One outworking of these emerging pre-occupations is the inhabited lobby – a central space in a building which connects different activities physically, visually, acoustically and socially.

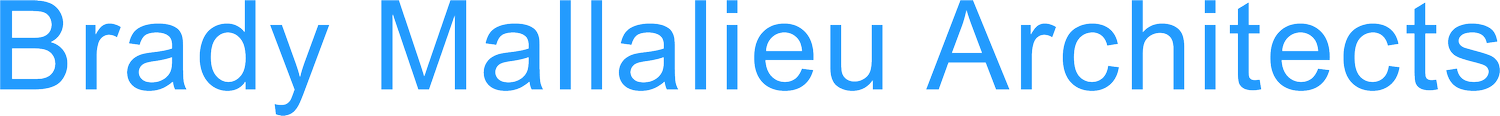

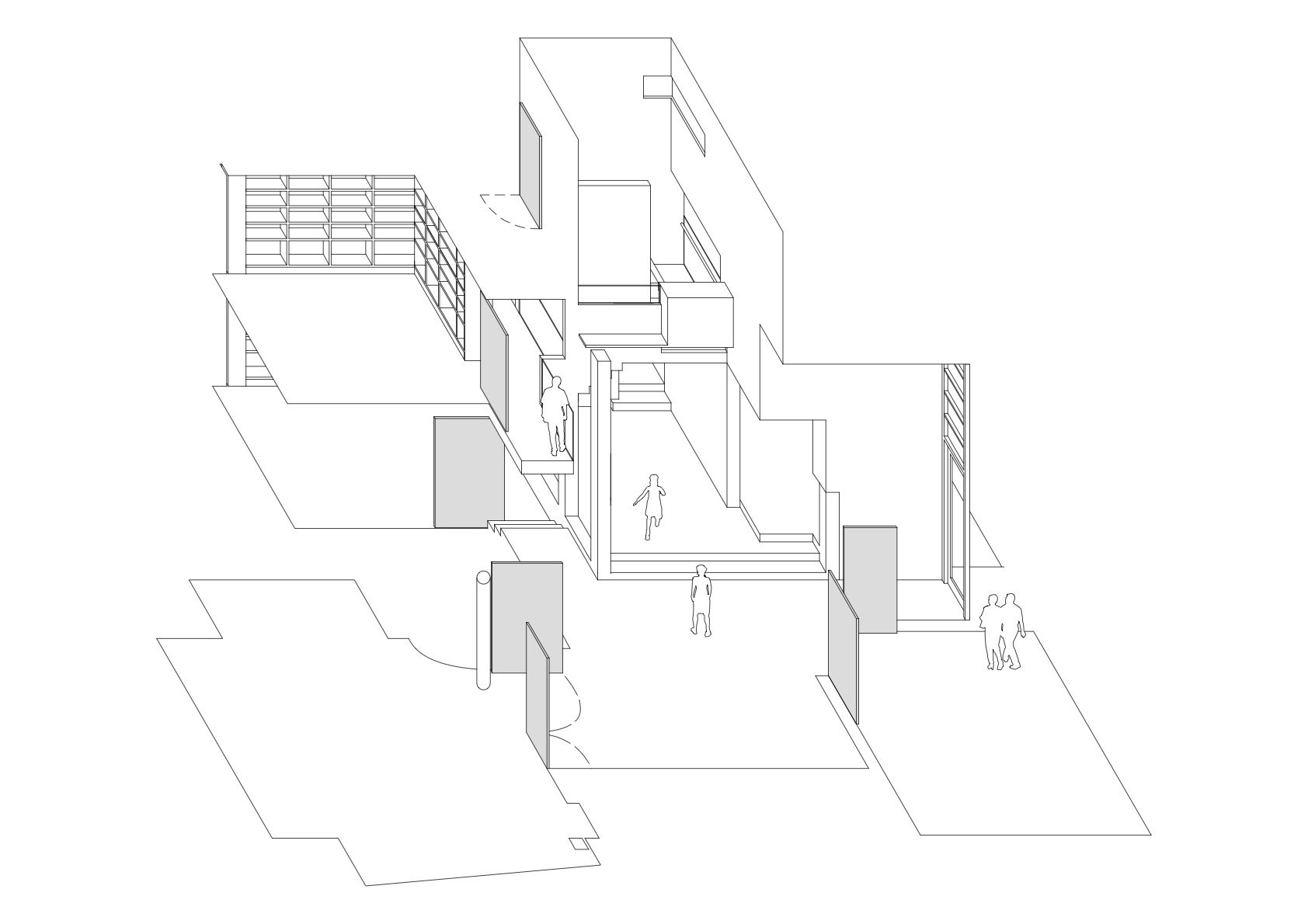

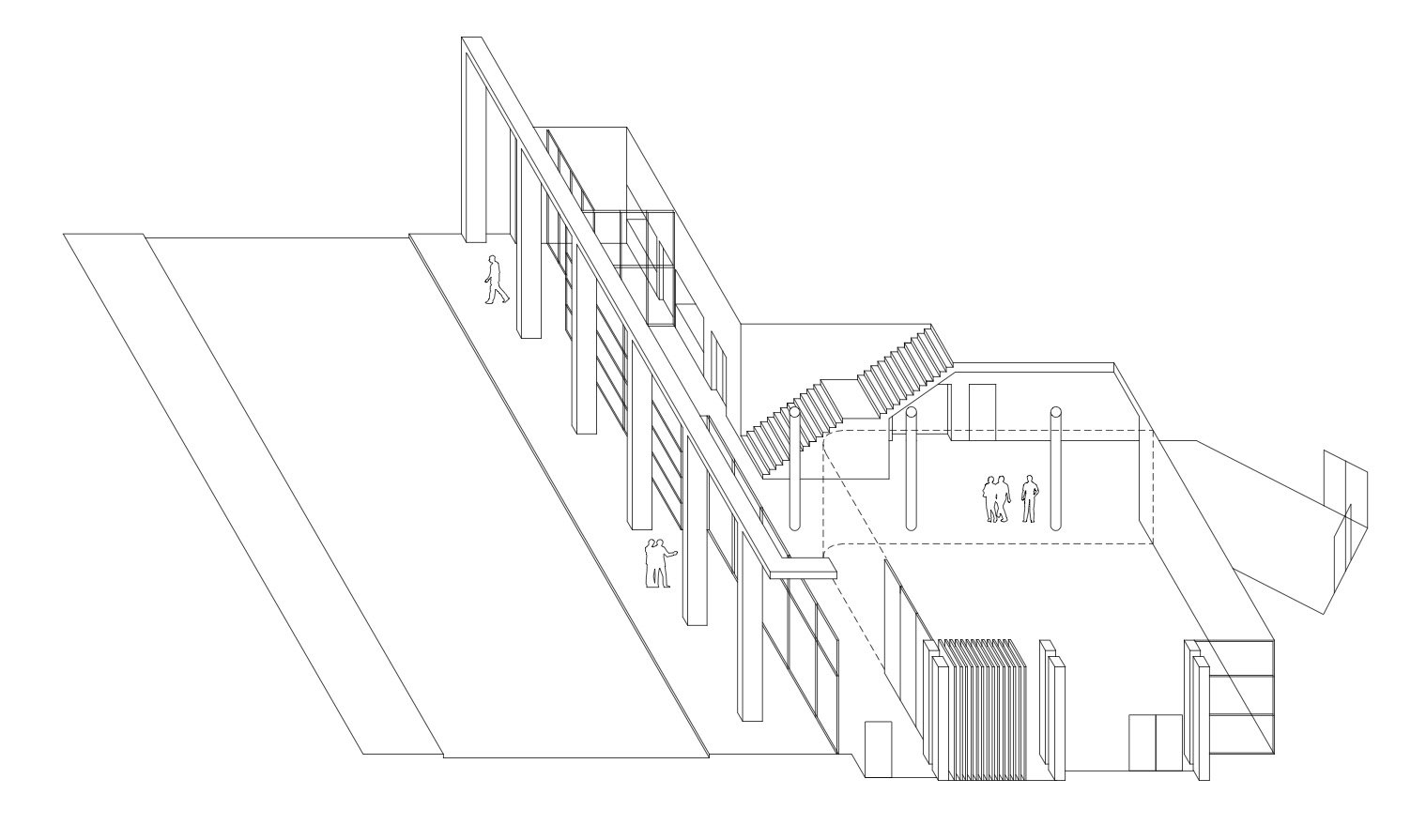

The device has been deployed and developed across a series of built and un-built projects ranging in scale from a private family home through various public buildings to a high-density housing complex. In 2016 we gathered these examples together in a peer-reviewed paper, published in arq to try and understand more about how these spaces work:

‘…The edges of these spaces serve a key role in negotiating the interactions and connections between the lobby and its neighbouring spaces. This may be as simple as an opening that allows a visual connection, as discussed above, and it can also be developed more richly. In some instances, this takes the form of intermediate and ambiguous spaces that blur the distinctions between one place and another or allow someone to be in one place but have a strong connection with another. Screens and doors are a key device, allowing adjacent uses and objects to spill into a lobby space and inhabit it. A rhythm might be given to the use of the lobby space by the opening and closing of these devices. The communal kitchen at Crouch Hill, for example, might open onto the lobby to demonstrate cookery skills to those assembled, or to serve refreshments at a gig, but when its doors are closed, other doors might open and it can serve as a play space or venue for a meeting. This rhythm of concealed and revealed spaces might equally apply to the objects that could inform how a space is inhabited or the capacity is has to host an event. Just as Peter Smithson praised the cupboard door for bringing the relevant objects into a space, as they might be required, from overlooked and neglected storage spaces, so too might adjacent spaces allow the lobby to adapt to the rhythms of its occupants: ‘Seasonally displayed objects packed away in boxes by the season, for Christmas… Easter…Bonfire Night…Halloween… A sewing machine… and of course, much, much more.

The combination of various spatial connections and devices is intended to enrich the potential for occupation, not only of the lobby itself but also the network of places which it connects together. Its underlying purpose is to make the building more habitable and engage with the unanticipated potential which a deterministic approach might overlook. The spatial strategies deployed are capable of being used in many ways, both planned and unplanned, and accompanied by props which invite and engage the user. The reality of how they will be used is, of course, impossible to predict.

The examples reviewed here trace a line of exploration by Brady Mallalieu Architects over nearly twenty five years. This has not always been a conscious exploration aimed at developing a particular spatial type and nor has it necessarily followed a linear path. In hindsight, the examples outlined here reveal similarities in approach and conception that create a pattern of connections. Ideas and components have recurred, suiting the requirements of different briefs and sites. But the central idea linking each example is a central space with horizontal and vertical connections that can become a point of interaction and exchange between activities. Notionally a circulation space, it assumes an expanded role becoming an inhabitable entity in itself. As much as it is a connecting, in-between space, it is a space in itself.’

The full text from our paper was published in arq/Architectural Research Quarterly as Inhabited Lobbies: The Social Life of Space in the Work of Brady Mallalieu Architects.